Theodore Clement Steele, American, 1847–1926

1906

Oil on canvas

76.24 cm x 101.6 cm | 30 in x 40 in

Framed: 137.16 cm x 111.76 cm x 8.89 cm | 54 in x 44 in x 3 1/2 in

Signed and dated lower right, T.C. Steele | 1906

Collection of Indianapolis Public Schools, on loan to Indiana State Museum

Abraham Crum Shortridge, (1833 – 1919), known as the “Father of Indianapolis Schools” was an important and progressive American educator and served as superintendent of the Indianapolis Public Schools (1863-1874). He also became the second president of Purdue University (1874-1875), which saw the matriculation of Purdue’s first students and awarded the first degree to a Purdue graduate. The second year, the university admitted its first female students and hired its first female instructor.

Shortridge was also instrumental in establishing the Indianapolis Public Library, Teachers Training School and under his leadership Indianapolis Public Schools opened to African-American children.¹

- Mary Alice Rann (1855 – 1914) was the first African-American student to graduate from Indianapolis High School, (named Shortridge in 1898). The school had 16 students of color by that time. Upon graduation in 1876, she attended Teachers College of Indianapolis, which became part of Butler University’s education department in 1930. After college, she established her career as an educator, and returned to the Indianapolis Public School where she taught until her retirement.

- Charity Dye (1870 – 1935), known for her activism for female suffrage and for peace, was a graduate of Teachers Training School (Normal School) and became an educator in the Indianapolis Public Schools for 37 years, distinguishing herself as an English teacher at Shortridge.¹ Eli Lilly, grandson of founder of Eli Lilly & Company (Pharmaceuticals) and president of Eli Lilly and Company from 1932 – 1948, was a Shortridge graduate and listed Charity Dye as his favorite teacher.

- May Wright Sewall (1844 – 1920) was an American educator and courageous reformer best known for her work and advocacy of women’s suffrage. She founded with a small group of women the Indianapolis Woman’s Club which encouraged a “liberal exchange of thoughts”. In 1888 she encouraged the Indianapolis Women’s Club to consider erecting a building to serve as a meeting place for the club and other literary, artistic, and social organizations in the city. This led to establishing the Indianapolis Propylaeum. She was a charter member of the Art Association of Indianapolis and the Herron Art Institute. May Wright Sewall taught German and English literature at Indianapolis High School from 1872 – 1880 (named Shortridge in 1898).

During Abram Shortridge’s eleven years as superintendent (1863 – 1874), the school system grew from 900 to 10,000 students and employed many female teachers. African American teacher Moses Broyles helped integrate the Indianapolis High School.

African-American Baptist minister Moses Broyles (c1826 – 1882), born a slave near Centerville, Maryland, sold to a master in Kentucky came to Indiana after his emancipation in 1851, to attend Eleutherian College in Jefferson College (later Craven Institute) from 1854 – 1857 (he was denied admissions to Hanover College). Broyles left college and moved to Indianapolis in 1857 to teach at one of the city’s first schools for African-American children. The city provided a building in the 4th ward for the subscription school, funded by student tuition or subscriptions, in response to school superintendent Abram C. Shortridge’s plea for education for African Americans in the city.¹

Indianapolis High School was founded in 1864 in two rooms of a grade school. It was the first high school in Indianapolis, and the first free high school in the state of Indiana. The school opened in the old Fourth Ward School on the corner of Vermont and New Jersey Streets. In 1898 the school was renamed Shortridge High School in honor of Abraham C. Shortridge.

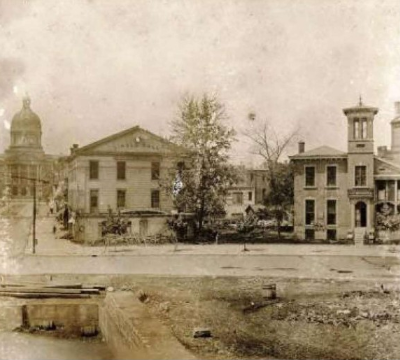

Abraham Shortridge proposed the organization of a high school for Indianapolis, but he reported to the board that it would take a year to bring even the most advanced pupils up to the level of high school work. Twenty-eight students, selected by examination, spent a year in preparation and then started actual high school work in the fall of 1865. They were taught by William A. Bell, principal, and one assistant, in two rooms of a ward schoolhouse (old Fourth Ward School) at Vermont and New Jersey streets. The school moved the following year (1866 – 1870) to the Second Presbyterian Church (once the pulpit for Henry Ward Beecher) on the northwest corner of Market Street and the Circle. Five of them graduated in 1869. Their diplomas read “Ad Astra per Aspera” – to the stars through difficulties.³

Indianapolis High School, northwest corner of Market Street and the Circle (1866 – 1870), note Indiana State Capitol in background (right photo)

In 1871, the school moved again to a larger building on the northeast corner of Michigan and Pennsylvania Streets. This building was once the spacious mansion of the Robert Underhill family. Underhill sold the home in 1858 to the Baptist Church, which was remodeled for use as the Baptist Young Ladies Institute. In 1871, the Board of School Commissioners bought the Institute and land, erected another building and used the mansion for the office of the Board of School Commissioners.

Indianapolis High School’s next move came after the city’s superintendent of schools recommended constructing a new high school building but the board voted on January 19, of 1883 that no new building or additions be built due to “financial embarrassment of the board”. However, in August architects were hired to ascertain the safety of the high school building and it was determined that it was indeed unsafe and recommended it be replaced. In 1884, the high school building was condemned and torn down. A new building was built on the site, and during the construction, classes were held in the Meridian Street Methodist Church at Meridian and New York streets and in Roberts Park Church at Delaware and Vermont.

The school board realized a high school would be needed on the south side, but until they could provide this, they used the new building on Virginia Avenue as an annex. This annex in School 8 on Virginia Avenue, which served the south side of the city and the German community, became known as “High School #2”. Students would attend High School #1 (Michigan and Pennsylvania) for their first three years of regular courses, and then would attend High School #2 (Virginia Avenue) for their senior year.

This would continue until Industrial Training School opened in 1895, which later became Manual Training High School (1899) and renamed Charles E. Emmerich Manual High School in 1916, in honor of its first principal of the industrial Training High School. The board also gave their approval of a new type of curriculum known as the “Manual Training Movement” that taught practical hand skills along with traditional classes.

Charles E. Emmerich ( first principle of Manual later named Emmerich Manual Training High School in his honor) saw a casual advertisement in a newspaper that caused him to come to Madison, Indiana in 1869 where he taught in the district schools. While in Madison, he wrote an article on “compulsory education”, which was published by the Indianapolis Daily Journal and caught the eye of Abraham C. Shortridge, then superintendent of the public schools of Indianapolis.

Mr. Shortridge corresponded with Professor Emmerich and invited him to a conference that resulted in a meeting where Professor Emmerich would join the faculty of the Indianapolis High School, as a teacher of Greek, Latin and German. Indianapolis High School later became Shortridge High School and Emmerich held this position for 19 years, most of which was teaching German.¹

Charles Emmerich became the first principal of Manual Training High School at the request of Abram Shortridge when the school opened in 1895. He excelled at implementing a new type of curriculum, with the blessing of the school board, known at the Manual Training Movement that taught practical hand skills along with the traditional classes.

Present day Shortridge High School, built in 1927, features Classical Revival architecture style and is located on 10 acres at 34th and Meridian Streets in Indianapolis, Indiana (3401 N. Meridian). The school is listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places.

Notable students were best-selling novelist Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., author Dan Wakefield, Senator Richard G. Lugar and best-selling authors Booth Tarkington and Meredith Nicholson also attended but were not graduates. Eli Lilly, grandson of founder of Eli Lilly & Company (Pharmaceuticals) was also a Shortridge graduate.

Abraham Shortridge was born in Henry County (Indiana) on October 22, 1833 and worked on his family’s farm until he was 18. He sold his only possession, his horse to get an education at Fairview Academy in Rush County, Indiana.² He was named for his maternal grandfather, Abraham Crum (1768 – 1836). He earned no college degrees and began his teaching career after a few months of study at the Fairview Academy and Richmond’s Greenmount College.

Abram Shortridge had a profound impact on building a public education system in Indianapolis and his legacy remains today in the city and at Shortridge High School. He struggled with vision for many years, but was known for his exceptionally strong work ethic and commitment to the Indianapolis Public School System.

“Mr. Shortridge had been blind for many years, and had never recovered from the shock of an accident that occurred thirteen years ago when he was run over by a traction car east of the city, suffering injuries that necessitated the amputation of his right leg.⁴

Shortridge’s poor health, near blindness, and disagreements with benefactor John Purdue (Purdue University) led Shortridge to resign from the university in December 1875. He then bought a farm near Indianapolis and became justice of the peace in Warren Township.

Abraham Shortridge died on October 8, 1919 at age 86. He lived with his son, Walter H. Shortridge, and the funeral services were held in this home at 5752 Lowell Avenue in Indianapolis. He and his wife Sarah Elizabeth “Sallie” Evans are buried in Crown Hill Cemetery, Section 15, Lot 74.

¹ Indiana Historical Bureau https://www.in.gov/history/2398.htm

²Hale, Michelle D. (1994). “Broyles, Moses”. In Bodenhamer, David J.; Barrows, Robert G., The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Indiana University Press. P 361. ISBN: 0-253-31222-1

³Shortridge High School, 1864-1981, In Retrospect, Laura Sheerin Gaus, Indiana Historical Society, 1985, ISBN-13: 978-0871950031

⁴The Indianapolis Star, 09 Oct 1919, Thursday, page 5